Bones of the Skull

The skull is a bony structure that supports the face and forms a protective cavity for the brain. It is comprised of many bones, formed by intramembranous ossification, which are joined together by sutures (fibrous joints). These joints fuse together in adulthood, thus permitting brain growth during adolescence.

The bones of the skull can be divided into two groups: those of the cranium (which can be subdivided the skullcap known as the calvarium, and the cranial base) and those of the face.

The Cranium

The cranium (also known as the neurocranium), is formed by the superior aspect of the skull. It encloses and protects the brain, meninges and cerebral vasculature.

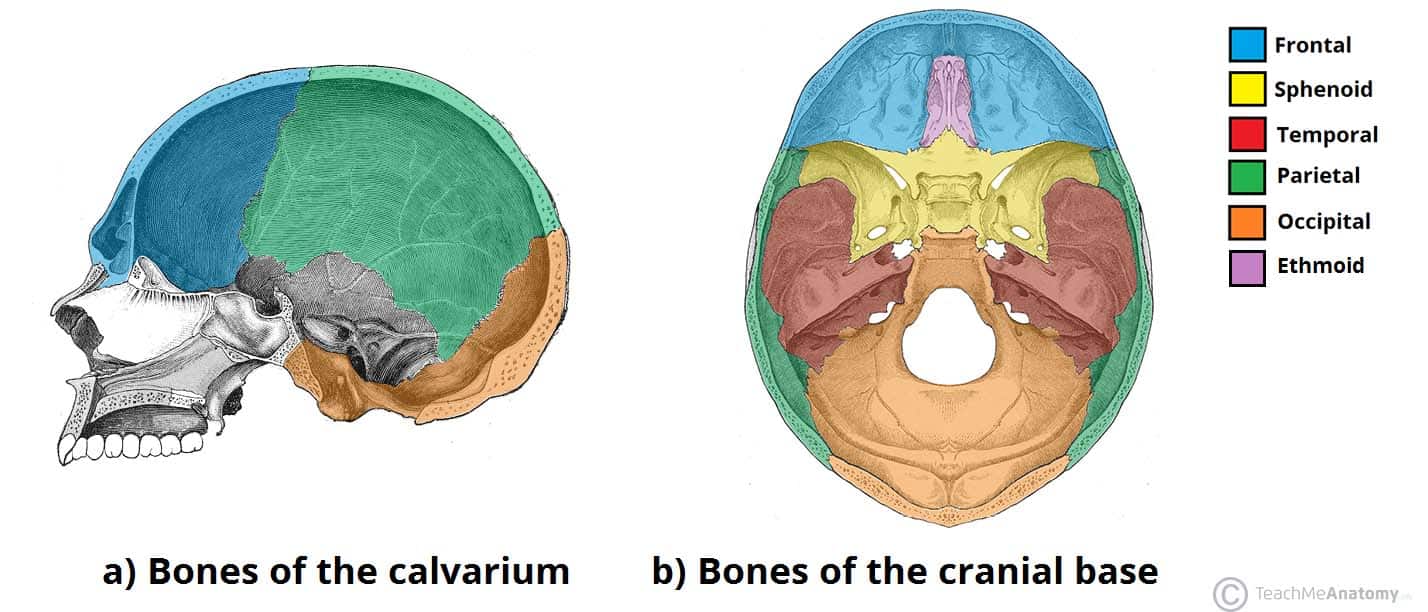

Anatomically, the cranium can be subdivided into a roof (known as the calvarium), and a base:

- Calvarium: Comprised of the frontal, occipital and two parietal bones.

- Cranial base: Comprised of six bones – the frontal, sphenoid, ethmoid, occipital, parietal and temporal bones. These bones are important as they provide an articulation point for the 1st cervical vertebra (atlas), as well as the facial bones and the mandible (jaw bone).

The Face

The facial skeleton (also known as the viscerocranium) supports the soft tissues of the face. In essence, they determine our facial appearance.

It consists of 14 individual bones, which fuse to house the orbits of the eyes, nasal and oral cavities, as well as the sinuses. The frontal bone, typically a bone of the calvaria, is sometimes included as part of the facial skeleton.

The facial bones are:

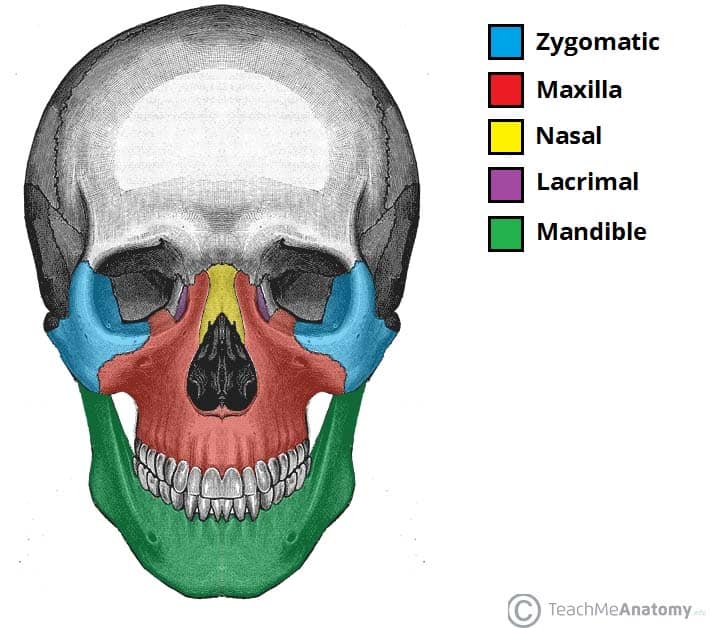

- By TeachMeSeries Ltd (2019)

Fig 1.1 – Anterior view of the face, showing some of the bones of the nasal skeleton. The vomer, palatine and inferior conchae bones lie deep within the face.Zygomatic (2) – Forms the cheek bones of the face, and articulates with the frontal, sphenoid, temporal and maxilla bones.

Fig 1.1 – Anterior view of the face, showing some of the bones of the nasal skeleton. The vomer, palatine and inferior conchae bones lie deep within the face.Zygomatic (2) – Forms the cheek bones of the face, and articulates with the frontal, sphenoid, temporal and maxilla bones.

- Lacrimal (2) – The smallest bones of the face. They form part of the medial wall of the orbit.

- Nasal (2) – Two slender bones, located at the bridge of the nose.

- Inferior nasal conchae (2) – Located within the nasal cavity, these bones increase the surface area of the nasal cavity, thus increasing the amount of inspired air that can come into contact with the cavity walls.

- Palatine (2) – Situated at the rear of oral cavity, and forms part of the hard palate.

- Maxilla (2) – Comprises part of the upper jaw and hard palate.

- Vomer – Forms the posterior aspect of the nasal septum.

- Mandible (jaw bone) – Articulates with the base of the cranium at the temporomandibular joint (TMJ).

Sutures of the Skull

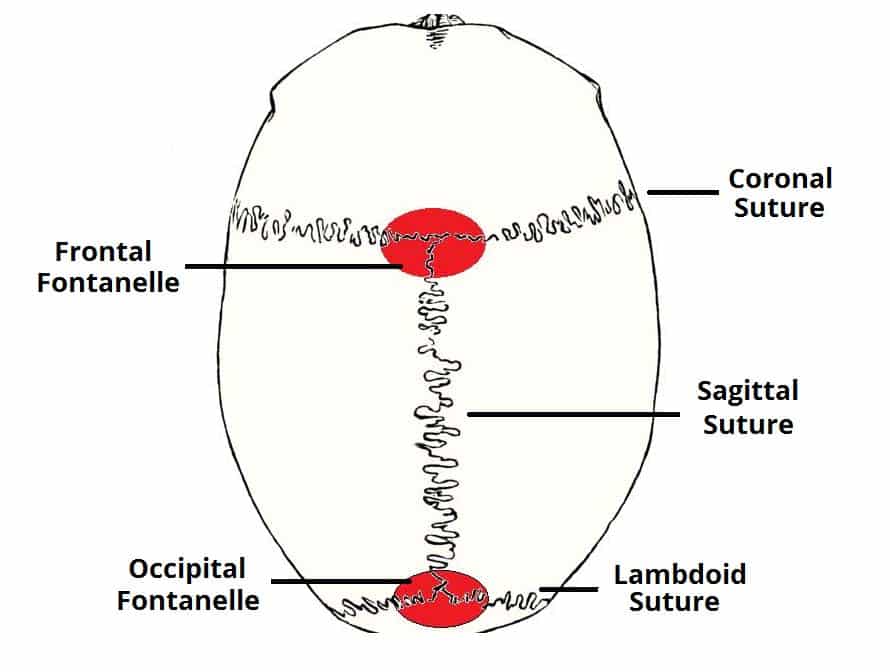

Sutures are a type of fibrous joint that are unique to the skull. They are immovable, and fuse completely around the age of 20.

Sutures are of clinical importance, as they can be points of potential weakness in both childhood and adulthood. The main sutures in adulthood are:

- Coronal suture which fuses the frontal bone with the two parietal bones.

- Sagittal suture which fuses both parietal bones to each other.

- Lambdoid suture which fuses the occipital bone to the two parietal bones.

In neonates, the incompletely fused suture joints give rise to membranous gaps between the bones, known as fontanelles. The two major fontanelles are the frontal fontanelle (located at the junction of the coronal and sagittal sutures) and the occipital fontanelle (located at the junction of the sagittal and lambdoid sutures).

Clinical Relevance: Cranial Fractures

The majority of skull fractures result from blunt force or penetrating trauma, and can produce numerous signs and symptoms. The clinical features may be obvious, such as visible injuries and bleeding. There are also subtle signs of fracture, such as clear fluid draining from the ears and nose (cerebrospinal fluid leak indicative of base of skull fracture), poor balance and confusion, slurred speech and a stiff neck.

There are certain areas of the skull that are natural points of weakness:

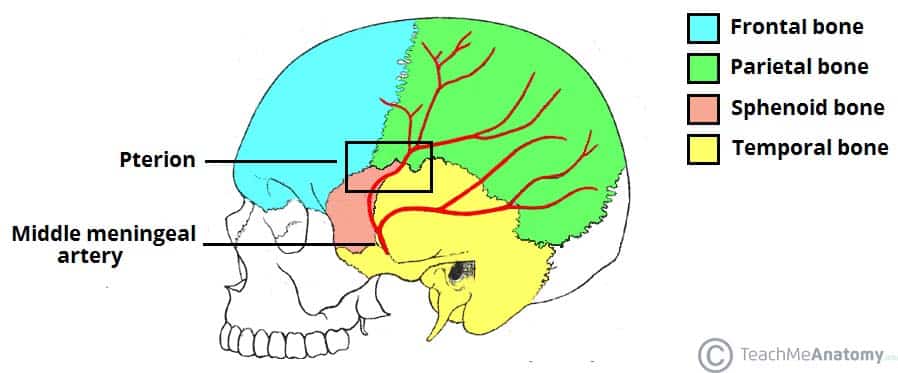

- The pterion: a ‘H-shaped’ junction between temporal, parietal, frontal and sphenoid bones. The thinnest part of the skull. A fracture here can lacerate the middle meningeal artery (anterior branch), resulting in a extradural haematoma.

- Anterior cranial fossa: Depression of skull formed by frontal, ethmoid and sphenoid bones.

- Middle cranial fossa: Depression formed by sphenoid, temporal and parietal bones.

- Posterior cranial fossa: Depression formed by squamous and mastoid temporal bone, plus occipital bone.

By TeachMeSeries Ltd (2019)

Fig 1.3 – Lateral view of the skull, showing the path of the meningeal arteries. Note the pterion, a weak point of the skull, where the anterior middle meningeal artery is at risk of damage.

Types of Fractures

There are four major types of cranial fracture:

By TeachMeSeries Ltd (2019)

Fig 1. 4 – Skull showing depressed fracture of the frontal bone, with linear fracture marked A

Depressed – fracture of the bone with depression of the bone inwards. They occur as a result of a direct blow, causing skull indentation, with possible underlying brain injury.

Linear – a simple break in the bone, traversing its full thickness. They have radiating (stellate) fracture lines away from the point of impact. The most common type of cranial fracture.

Basal skull – affects the base of the skull. They characteristically present with bruising behind the ears, known as Battle’s sign (mastoid ecchymosis) or bruising around the eyes/orbits, known as Raccoon eye’s.

Diastatic – fracture that occurs along a suture line, causing a widening of the suture. They are most often seen in children.

By RosarioVanTulpe [CC-BY-SA-3.0] via Wikimedia Commons

Fig 1.5 – Le fort classification of maxillary fractures

Clinical Relevance: Facial Fractures

Facial fractures are common and generally trauma related, i.e. road traffic collisions, fights and falls. They are often associated with clinical features such as profuse bleeding, swelling, deformity and anaesthesia of the skin. The nasal bones are most frequently fractured, due to their prominent position at the bridge of the nose.

A maxillofacial fracture is one that affects the maxillae bones. This requires a trauma with a large amount of force. Facial fractures affecting the maxillary bones can be identified using the Le Fort classification, depending on the bones involved, ranging from 1 to 3 (most serious).

Comments

Post a Comment