The Pharyngeal Arches

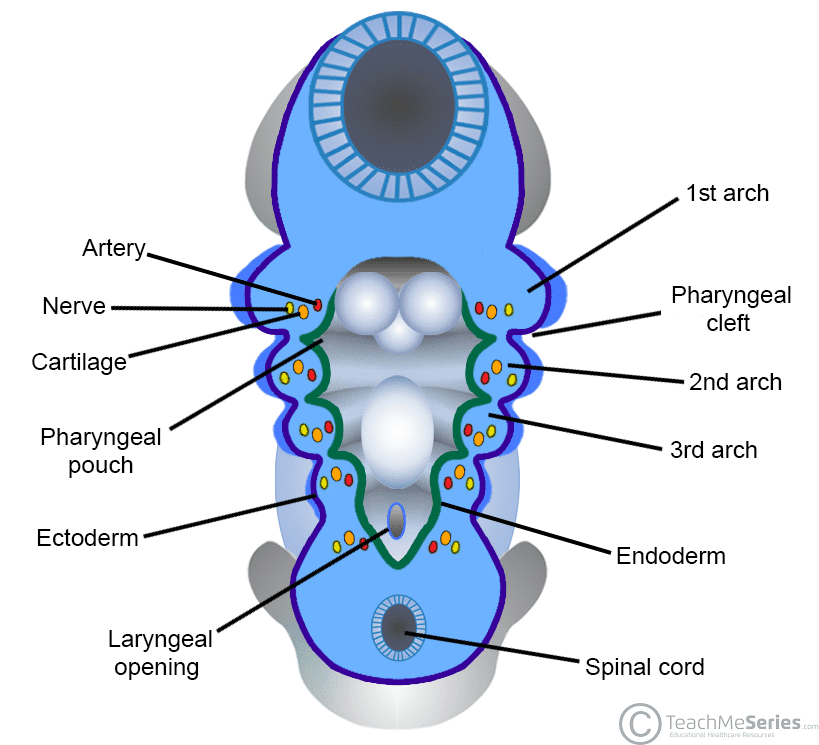

The development of the head and neck begins in the 4th and 5th week. Growth of mesenchymal tissue (connective tissue) in the cranial region of the embryo results in the formation of arches, separated by clefts. These are the pharyngeal arches and pharyngeal clefts.

Simultaneously, a number of out-pocketings appear on the lateral wall of the pharynx – the pharyngeal pouches. The pouches separate the arches on the internal (endodermal) surface whilst the clefts separate the arches on the external (ectodermal) surface.

In this article, we will explore these structures from outside to inside and discuss the structures that arise from the pharyngeal apparatus.

(Note: In older texts, the pharyngeal clefts/arches/pouches are referred to as the branchial clefts/arches/pouches)

Pharyngeal Clefts

There are initially four pharyngeal clefts. However, only the 1st cleft gives rise to a permanent structure in the adult; the external auditory meatus.

The 2nd, 3rd and 4th clefts only form temporary cervical sinuses – which are then obliterated by the rapidly proliferating 2nd pharyngeal arch.

Pharyngeal Arches

There are six pharyngeal arches – however, the 5th regresses soon after forming.

Each arch is innervated by an arch-associated cranial nerve, and has a muscular component, a skeletal and cartilaginous supporting element. as well as a vascular component.

In the adult, each pharyngeal arch is associated with specific structures within the head and neck.

First Arch

The first pharyngeal arch is comprised of two parts:

- Maxillary prominence (dorsal portion) – becomes the future maxilla, zygomatic bone and part of the temporal bone.

- Is associated with the maxillary cartilage, which gives rise to the incus.

- Mandibular prominence (ventral portion) – becomes the future mandible.

- Is associated with Meckel’s cartilage, which gives rise to the malleus and the sphenomandibular ligament.

The artery of the first pharyngeal arch becomes the terminal portion of the maxillary artery, which is a branch of the external carotid.

Its associated nerve is the trigeminal nerve (CN V). The first arch gives rise to the muscles of mastication, and also the mylohyoid, the anterior belly of digastric, tensor veli palatani and tensor tympani – all of which are innervated by the branches of the trigeminal nerve.

Its sensory field is that of the trigeminal nerve too, namely the skin of the face, the lining of the mouth and nose, and general sensation to the anterior 2/3 of the tongue.

Second Arch

There are two arteries associated with the second pharyngeal arch:

- Stapedial artery – connects the embryonic precusors of the internal carotid, internal maxillary and middle meningeal arteries. It regresses before birth.

- Hyoid artery – gives rise to the corticotympanic artery in the adult.

Reichart’s cartilage is the name given to the cartilage component of the second arch. It is the precursor to the stapes, the styloid process, the stylohyoid ligament and the upper body and lesser horn of the hyoid bone.

The nerve associated with the second pharyngeal arch is the facial nerve (CN VII). It innervates all the muscular derivatives of the 2nd arch – the muscles of facial expression, stapedius, stylohyoid, platysma and the posterior belly of digastric.

The sensory field of the second arch is that of the facial nerve, namely taste sensation to the anterior 2/3rds of the tongue (via the chorda tympani).

Third Arch

The artery of the third pharyngeal arch becomes the common carotid artery and the proximal portion of the internal carotid artery.

Its cartilaginous component is less complex than the first two arches, and gives rise to only the lower body and greater horn of the hyoid.

Its associated cranial nerve is the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX).

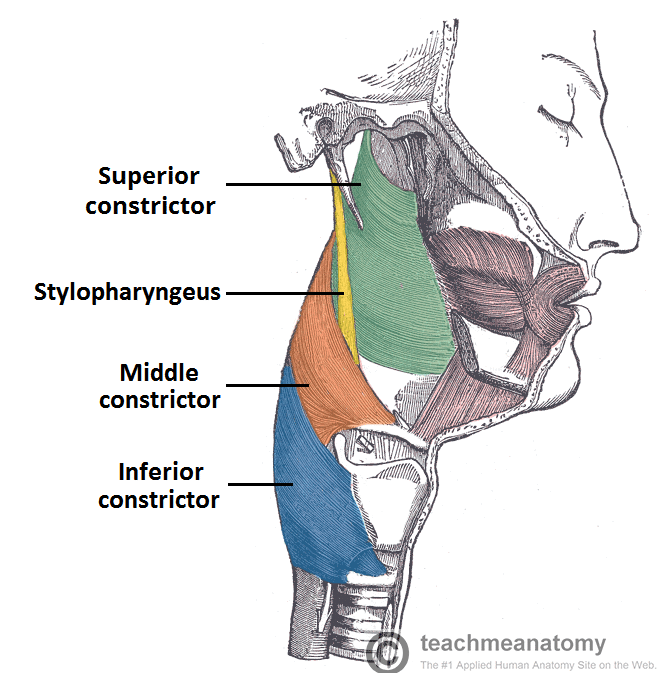

The third arch gives rise to stylopharyngeus, and its sensory function is to provide taste and general sensation to the posterior 1/3rd of the tongue.

Fourth Arch

The vascular derivatives of the fourth pharyngeal arch differ between the left and right:

- Right – proximal portion of the subclavian artery

- Left – aortic arch

The fourth arch gives rise to laryngeal cartilages – namely the thyroid, corniculate and cuneiform cartilages.

The associated nerve is the superior laryngeal branch of the vagus nerve (CN X), which innervates the muscular derivatives of the fourth arch; the constrictors of the pharynx, levator palatini and cricothyroid.

Innervation to the root of the tongue is provided by the superior laryngeal branch.

Sixth Arch

The vascular derivatives of the sixth pharyngeal arch differ between the left and right:

- Right – proximal portion of the pulmonary arteries

- Left – ductus arteriosus

The associated nerve is the recurrent laryngeal branch of the vagus nerve (CN X). It innervates the intrinsic muscles of the larynx (with the exception of cricothyroid), which are derived from the sixth arch.

The sensory field of the recurrent laryngeal branch is widespread. It includes taste sensation from the epiglottis and pharynx, general sensation in the pharynx, larynx, oesophagus, tympanic membrane, external auditory meatus and part of the external ear. It also provides the efferent limb of the gag reflex, and parasympathetic innervation to viscera.

By TeachMeSeries Ltd (2019)

Fig 3 – The intrinsic muscles of the larynx are derived from the sixth pharyngeal arch.

Pharyngeal Pouches

The pharyngeal pouches separate the pharyngeal arches on the inner (endodermal) surface. There are five pairs of pouches, with only four giving rise to adult structures.

Below is a table summarising the derivatives of the branchial pouches:

| Arch | Derivatives |

| 1st | Eustachian tube and middle ear cavity |

| 2nd | Lining of the palatine tonsils |

| 3rd |

|

| 4th |

|

Clinical Relevance - Branchial Cyst

If the pharyngeal clefts are not obliterated by the 2nd pharyngeal arch, they can persist into adulthood as branchial (pharyngeal) cysts.

They are typically located in the lateral aspect of the neck, arising at any point along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. These cysts may intermittently swell, particularly in association with upper respiratory tract infections.

Definitive treatment is surgical excision, but this is not indicated in all cases.

Comments

Post a Comment